Now you can also like my facebook page "In Bed With the Tudors"- updates about the forthcoming book and little juicy snippets of intimate Tudor life.

Amy Licence: historian of the lives of Medieval, Tudor and early modern women; nineteenth and early twentieth century art, history, literature and culture; writer of literary ficton.

Sunday, 1 April 2012

"In Bed With the Tudors"

Women bathing, from a fifteenth century Italian Manuscript. How regularly you bathed depended on your social class but many mixed, public baths sprung up on the Southbank. Their association with prostitution soon brought them into disrepute and they were frequently closed during outbreaks of plague and other diseases. Henry VIII finally closed them down in the 1540s.

Now you can also like my facebook page "In Bed With the Tudors"- updates about the forthcoming book and little juicy snippets of intimate Tudor life.

Now you can also like my facebook page "In Bed With the Tudors"- updates about the forthcoming book and little juicy snippets of intimate Tudor life.

Monday, 19 March 2012

"In Bed With the Tudors."

My new book, due out in July-

"In Bed With the Tudors: The Sex Lives of a Dynasty, from Elizabeth of York to Elizabeth I ."

Amy Licence, Amberley Publishing, 28 July 2012.

Available to pre-order on Amazon now.

What was it like to bear the child of a Tudor king? How did Queens cope under pressure, knowing the future of the realm rested on their shoulders ? What comforts did they find in religion and birthing customs, in an era predating pain relief ? What steps did midwives take, to ease a prince or princess into the world ? And what about the "average" Tudor woman, if such a thing existed ? How did she prepare for her lying-in and what chance of survival did she and her child face ? Then there are the numerous disenfranchised; the peddlar delivering her child in a barn and the serving girl seduced by her master. How did society deal with them once their child provided the living proof that they had transgressed the strict social boundaries of the time?

When it came to parenthood, the Tudor monarchs were unlucky. Maternal and infant mortality were high. Henry VIII's wives were beset by a range of gynaecological problems that contemporary medicine and religion were powerless to unravel, no matter how many remedies and cures they tried. From powdered ant's eggs, to the skin of a wild ass tied to their thighs, labouring women were at the mercy of fate and poor hygiene. Giving birth was a life or death experience and survival was cause for celebration. This book details the experiences of Queens, royal mistresses and ordinary women of all classes, from fertility, conception and pregnancy through to the delivery chamber, lying-in, baptism and churching. Set against the backdrop of immense cultural and religious change, the story of reproduction between 1485 and 1603 is also a story of the Reformation and sudden banning of centuries-old customs that had been relied upon by women in the birthroom for generations. The importance of pilgrimage and the monastic establishment in the reproductive process has never before been explored, yet their dissolution had a huge impact on the lives of millions of women. Some conformed, some resisted. Giving birth was also a critical part of the Tudor gender dynamic and frequently polarised the sexes; feminine exclusivity and oral traditions were set against the misogyny and suspicion that overdetermined the culture of the times. Literally and metaphorically, the doors were closed upon the men.

Predictably, marital status was all important to the Tudors. This did not mean it was not an honour to bear the King's bastard but it guaranteed little. The circumstances of conception and birth differed greatly depending upon a child’s legitimacy, as did the expectations of its mother. Explored in this book are the implications of both experiences, as well as the roles of midwives and gossips, the limits of Tudor medicine and the implications for the dynasty of infertility, incompatibility, adultery and the elective abstinence that led to the decline of the royal line. After the birth of Edward in 1537, no Prince was born on English soil until Charles II in 1630. Mary I's infertility and Elizabeth's notorious virginity kept the nation guessing for half a century. How did other women deal with a failure to conceive ? Some prayed, whilst others employed sympathetic magic or bizarre folkloric rituals. The business of producing an heir was never straightforward; each woman’s story is a blend of specific personal circumstances, set against their historical moment: for some the joys were brief, for others, it was a question that ultimately determined their fates. In a society that prescribed a few, limited female roles, the failure to fulfil her maternal obligations was the making or breaking of Tudor women.

Were their experiences significantly different to those of mothers today ? Yes and no. This book explains why.

Tuesday, 6 March 2012

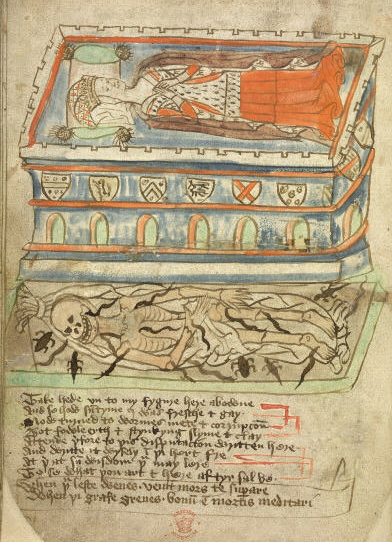

Medieval Memento Mori Tomb

Just wanted to share this wonderful fifteenth century manuscript illustration depicting a rich lady atop her tomb with her decaying bones beneath.

Fewer posts going up at the moment as the deadline for my book approaches- be back soon !

Tuesday, 14 February 2012

A very short history of 500 years in the garden.

German Garden, 1410.

Gardens and domestic outdoor spaces have always been a feature of our lives. Most Tudor homes had a garden of some sort, or else some land attached, even in the middle of a city like London. Their use was heavily dependent upon class, either to supplement the table and produce essential medicinal herbs or as arenas to display luxury and status. Native fruit and vegetables in season could make a huge difference to a lower-class family's diet and the cultivation and use of herbs, a remnant of the medieval monastic tradition, came from a rich oral tradition of home cures for every eventuality. Many were functional living spaces too, used for all manner of domestic work, including washing and drying, although fields outside the city walls were also emplyed in this way. Palace gardens were resplendent with statues and ornaments; the garden at Whitehall contained gilded heraldic beasts whilst at Kenilworth, the gardens became the famous stage for Elizabeth I's visit, remodelled with fountains, lake and island. There was little concept of garden design outside upperclass circles, with outdoor spaces being maximised for their productive abilites, as well as the exercise of man and beast. However, small knot gardens, full of scented herbs and plants were made along intricate lines and not beyond the reach of the middle classes. Their symmetrical designs, redolent of early Persian gardens, are the most archetypal of Tudor garden survivals..

A knot garden, recreated at the Garden Museum, Lambeth.

Seventeenth century gentlemen, returning from the grand European tour, brought back an appreciation of dramatic natural geographic features. "Sublime" mountains and Alpine-style lakes became all the rage. Mock Graeco-Roman ruins were imported into English landscapes, crumbling away among parks like that at Windsor. Completely new follies were built and artifically aged. Formal gardens betrayed Dutch and Italian influences too, balancing areas of symmetry and order with areas of wilderness to express the sublime power of the natural world. Specific areas were tamed into avenues, topiary creations, terraces and waterworks, whilst others, often distant were left to grow wild as described in Austen's Mansfield Park. Contained within the garden's confines, her jumbled-up pairs of lovers manage to contain their lusts but the temptation of entering the wildeness through the locked gate proves their undoing. Blenheim, Hampton Court and Versailles all demonstrate this balance between the careful, man-tamed environment and the wilderness beyond. It was to give an illusion of connection between the two, whilst allowing a degree of protection, that the sunken ditch known as the ha-ha came into use as a boundary. The garden became a playground, spurting jets of water among statues and using straight lines to create outdoor rooms. Poems by Andrew Marvell contrast the wild world inhabited by the mower with the formal yet playful environment of the great house. The abundance of flowers, fruit and vegetables he mentions are typical of the new methods of gardening, where exotic plants from the new world were grafted and unseasonably forced in large greenhouses and new colours blended and created. For the wealthy, it was an era of orangeries and tulips.

Badminton Morris House, Gloucestershire, with its deliberately "undesigned" park design.

The natural look became increasingly prevalent in the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth centuries, with vast parks being swept clean of unsightly features like villages; wavy lines, trees and grass growing freely with grazing sheep echoed an aristcratic preoccupation of the European bucolic ideal, such as epitomised in the novels of Anne Radcliffe, paintings of Claude Lorrain and romantics like Samuel Palmer and Caspar David Friedrich. Capability Brown worked on over 170 gardens in England during this time, advocating a "gardenless" form of gardening; his works survive at Coombe Park, Warwick Castle and Bowood House among others. Again, class was significant. Outdoor spaces became increasingly public and the vast parks of cities like London, Paris and Vienna became the locations for Sunday family promenades as well as political rallies.The old eighteenth century pleasure gardens, with something of an unsavoury reputation, as in Thackeray's Vanity Fair gave way to the more genteel tea gardens depicted by the Post-Impressionsts. Huge market gardens produced fresh fruit and flowers which the spread of railways allowed to grace city dining tables of the rich. With more produce becoming available, gardens became increasingly about relaxation and the achievement of a casual, meadow-style look. Native plants were sown with apparent abandon, to create the impression of self-seeding in what was actually careful planning, by cottage-garden designers such as Gertrude Jekyll. Her romantic, pretty planting with its subtle colours and blowsy borders was developed by other early twentieth century enthusiasts like Vita Sackville-West. The romance and escape of gardens was popularised by the 1909 best selling "Elizabeth and her German Garden" and its sequels, by Elizabeth von Arnim.

Gertrude Jekyll border at Manor House, Upton Grey, Hampshire

The Twentieth century saw garden design becoming increasingly architectural. Unusual features and play between the natural and man-made are popular again, as any visit to Hampton Court Flower show will demonstrate. Large panels of synthetic materials in bright colours sit along side rustic-style modern follies, whilst a wealth of innovative planting allows for exciting contrast and variety in texture, scent and colour. Features like decking, patios and planting boxes allow even small gardens to maxmise their space, providing an extra room in over-crowded urban areas. The popularity of conservatories has seen them change from the overwhelmingly green waxy-leaved hot houses of the Victorian upper classes, with their heavy furniture, to lighter, open spaces that combine the best of indoor and out. Cheap garden fittings, furniture, plants and barbeques encourage us to get outside as much as possible, whilst TV makeover and DIY programmes give cheap inspiration regarding the transformation of our backyards. In a complete reversal from their use by our grandparents, to house Anderson shelters and dig for victory, gardens have become our arenas for experimentation and self-expression. In the modern garden, anything goes.

Electric car on display at the 2009 Hampton Court Flower Show

Saturday, 28 January 2012

Who's the daddy ? Scandal in Elizabethan Essex.

These days, paternity can be easily ascertained using DNA testing. Four hundred years ago, the question was far more complex, often pitting the word of a woman against a man. As the care of an illegitimate child usually fell to the parish, it was important to establish, if possible, who the most likely father was and to make them support their offspring. In search of the truth, the whole community could get involved. Everyone seemed to have some insight or evidence to offer and hearsay or the good "reputation" of those concerned was considered crucial. This could open the wounds of old grievances and scandals. The case of Mary Graunte, a spinster of Colchester, provides a really good example of the way illegitimacy cases were conducted.

The Easter Chelmsford Court Sessions of 1601 heard tell of a child born to spinster Mary Graunte, who she claimed had been fathered by a Thomas Carter of White Colne. The complicated twists and turns, rumour, reported conversations, multiple witnesses and mixing of the claims of paternity, loans and debts, illustrates the very public dimension of pregnancy and the roles of those involved. Justices Sir Roger Harlakinden and Thomas Waldegrave led the examinations, starting with evidence concerning Carter. Apparently, Mary had already been examined by a panel of matrons, upon her pregnancy becoming public. This was common practice, although not fool-proof, as ascertaining that conception had taken place was not an exact science. She must have undergone an intrusive physical inspection, when quite advanced in her pregnancy, as if the stigma of illegitimate conception had made her an open target for all other sorts of invasion and losses of dignity.

At that stage, Mary had refused to name the father, although she claimed he had agreed to pay her maintenance so long as she concealed his identity. He had told her that if she were to name him, he would give her nothing “but grow to utter defiance and dislike of her.” However, the minister of East Colne, a Mr Adams, then got involved, as men of the cloth frequently did in such cases, either for good or bad. Adams tried to persuade her to confess, upon which she gave him a clue in a description of Carter’s mother, whom Adams had buried a few years before. She then described Carter to him as having been a “serving man and park-keeper and a butler and had but one eye;” which left Adams in little doubt about who she meant, as all the “circumstances of the description do fitly fall out.” Adams must have communicated these findings, as Mary was then re-examined and admitted Carter was the father and told the story of their courtship. In less than romantic terms, she described how he had had “the use of her” twice around Lent and a third time after Easter last, after which the acquaintance had developed in the household of Carter’s uncle, where Thomas was living at the time and Mary was an accustomed visitor. So far it seemed a fairly straightforward case with Carter as the child’s father.

The Justices then called upon the women who had attended Mary during her lying-in, her midwives and assistants, or "gossips." They may have been her friends; some were certainly her relations. In the court records, these women defined by their marital status and given a social identity by men, as whose instruments they appear to be here: the widow Margaret Pullen; Barbara Prentice, wife of John; Florence Ford, wife of William; Joan Carter, wife of Robert, uncle of the accused; Jane Saunderson, wife of Thomas and the widow Margery Edwards. Ordinarily, female evidence in the law courts was received with suspicion and subject to social standing: Swinburne claimed their inadmissibility because of “inconstancie and frailty” at the end of the Tudor period. However, when it came to cases of paternity, a reversal of the norm saw midwives at the centre of bastardy suits; male reluctance to condemn based on the world of females alone, would have also affected the parity of justice meted out. Mary’s case was typical. These women gave their oaths that whilst she was in “the extremity of her pain and travail” they had charged Mary to betray the father or else they would not help her, which seems a remarkably unsympathetic threat if they would have carried it through. In response, she called out the name of Thomas Carter, which she repeated during and after her delivery. Carter’s aunt Joan then added for good measure that Mary owed her 3s and a bed sheet lent to her a fortnight before her labour.

Mary’s own mother was then called for questioning; one widow Margaret Claypoole of Earls Colne. She described how Thomas Carter had repeatedly denied paternity and that her daughter knew she would receive no money from him if she were to accuse him. A Margery Tailor, wife of William, then told the court how she had been with Mary during her lying-in, when the new mother had “made great mone, (moan)” saying that she would now get no relief from Carter, having confessed his identity and “cried woe to the bones of him”, wishing they had never met. She told Margery that if Carter had kept promise with her, she would never had betrayed him though she be “racked to death” and could have had a child by him long before this, if she had consented.

Carter himself was then pulled in for questioning. He appears to have had some influence over the process, drawing in a staggering number of witnesses in an attempt to identify other potential fathers and exonerate himself. At his suggestion, Mary was asked about a statement she made that the father of her child visited her on foot rather than horseback. She had claimed he need not ride, living so nearby that she saw him out walking every day. This was corroborated by a John Warde, who had heard her say so, although this does not seem to have assisted Carter’s case in any way. Then Carter suggested Mary be examined regarding a plea she made for help to one Robert Reade, claiming she would otherwise receive nothing from her child’s father: Reade, present at the examination, denied this upon oath, as did John Dikes and his wife Margaret, whom she had also supplicated. In Mary’s favour, a Thomas Healy swore he had heard the conversation take place at “Old Reade’s,” so somebody was not telling the truth. A widow Agnes Kinge then claimed that one Thomas Allen knew the identity of Mary’s child’s father; Allen and Helen his wife denied this and a subsequent charge of offering Mary ten pounds in support. A Robert Rooke then deposed that Agnes Kinge believed Allen to be the child’s father and that she had gone to him when she was called for her initial examination and a Mary Sparrowe stated how Mary had received other money from Allen. Apparently one Frances Gergrave had been the go-between but Allen stated he had only paid her for her spinning work. Allen also said Mary Sparrow had stolen herrings from him and that he had also lent her money, so she had cause to speak against him. Sparrow confessed that Carter had tried to bribe her to say something good about him. The cast list grew longer and the plot thickened.

Carter seemed desperate to clear his name, which is neither indicator of guilt or innocence. As the father of an illegitimate child, he may have been willing to try anything to avoid responsibility, especially if it caused him trouble with his family and/or employer. Equally, as an innocent man, he would not wish to have his name tainted by someone else's scandal, perhaps affecting his social standing, business and even future marital prospects. Keen to defend himself, he went on to claim that a Thomas Turner would wager 40s that Carter had been wronged and that an unknown man had ridden with Mary on horseback behind Turner and lain with her at Carter’s house. However, Turner denied this when before the court. Was it a bribe ? Turner’s brother, one Clement, then described how when Turner returned home from the sea, Mary fell to her knees before him saying that if he had been gone she would have “raised town and country after you;” also that Allen told him he had lain with Mary at the house of Nicholas Grigges of Donyland, when they had pretended to be man and wife. Grigges claimed Mary had lain with a man he did not know in a trundle bed beside the very bed where he slept that night with his wife ! Such beds were often stored and used in close proximity by masters and servants. If anyone knew what had happened, it would have been the Griggeses!

The outcome of this complex case is unclear but the numbers of people involved and the surfacing of many accusations of bribery, secrecy, theft and false confessions is indicative of a small, close community, ready to side against each other. Sadly, little mention is made of the child in all this legislation. Many children did not survive beyond their first year, given the dangers of illness and disease. Its probable fate, as with so many illegitimate children of the era was to be raised by the parish and placed at an early age in service or an apprenticeship. The fates of Mary and Carter are unknown.

Thursday, 19 January 2012

Artquake, 1910: The show that shocked London.

Modern artists are no strangers to controversy. So many boundaries have been pushed and pulled, so many dimensions explored and taboos broken that we’ve come to expect our art to be provoking. In fact, we expect nothing less; such works command thousands, millions. But it wasn’t always the way. In London, just over a century ago, the biggest storm in the history of English art was about to break, with our most famous and cherished artists of today relegated to the status of a freak show.

Virginia Woolf’s often quoted comment that “on or about December 1910 human character changed”, reminds us of the impact the first Post-Impressionist exhibition had upon public consciousness. England had barely been touched by the artistic revolution raging across the Channel, with middle class tastes set by the traditional teaching of the Royal Academy. At the time it would not have been possible to predict the “artquake” that was about to drag England unexpectedly and belatedly into the modernist era. Significantly, the newly powerful Edwardian Press were to play a key role in the fervent dialogue that sprung up in the show’s wake. Public responses would range from disbelief to the hysterical and those involved were to find themselves the targets of censure and hostility for challenging the very definition of art and national identity. For better or worse, Post-Impressionism was about to seize the public imagination.

Roger Fry, self portrait

The show was the brainchild of Bloomsbury artist and critic Roger Fry, although until shortly before, even he had remained unconvinced by the new art and firmly wedded to tradition. Since 1906, Fry had been Curator of Paintings in New York’s Museum of Modern Art and envisaged an Anglo-American future for the arts, rather than with his European contemporaries. He was first impressed by Cezanne’s work at an International Society exhibition in 1906, although damned it with faint praise, admitting they were at least “complete” and had “power.” By 1908, he was writing in the Burlington Magazine that Cezanne’s position was assured and that the art of Gauguin, Denis and Signac also offered an “expressive alternative to the Impressionists’.” However, he could still not accept the European use of bright colours, reacting in bafflement to the colours in a work by Moreau, whilst admitting that it “must be possessed of a quite astonishing artistic intelligence…yet for the present, I do not quite see it. I can suppose myself capable of seeing it; I can argue that I ought to; but I still fail.” His own 1909 one man show at the Carfax Gallery presented a typically English palette of browns, blues and greys, gently criticised in the Times for its colours:” “a land of everlasting twilight would be a dreary place” and the Morning Post for inaccessibility: “people will have to be under its influence for a time to appreciate its beauty.”

Something changed though. The following year saw Fry’s focus shift from past to present and a desire to breathe new life into the modern art movement; writing to William Rothenstein in January 1910, he announced “I feel a new hope altogether about art…all those who care and are not fossilized must get together and produce something.” A chance meeting on a railway station platform that month provided the opportunity.

Vanessa Bell by Roger Fry

At Cambridge Station, awaiting the London train, Bloomsbury artist Vanessa Bell introduced herself and her husband to Fry, in a move that was to have immense repercussions for the impact of European avant-garde art upon London. Clive Bell had developed an interest in art independent of his wealthy “hunting, shooting, fishing” family who had made their fortune in coal; Cambridge friends had been impressed by a reproduction Degas hanging in his room: in 1904 he had visited Paris ostensibly to research a paper, yet spent all his time at the Louvre. Vanessa, the elder sister of Virginia Woolf, had received some formal training at South Kensington Art School, the Slade and the Royal Academy School but social ties gave her wider connections, including radicals like Walter Sickert and society portraitist John Singer Sargent.

Towards the end of that year, when Fry was asked to organise an exhibition for the Grafton galleries, he “seized the opportunity to bring before the English public a selection of works conforming to the new direction.” Part of the problem was the wide range covered by these artists; no coherent style united them, it was simply their simultaneity that prompted Fry to choose their name. “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” included two hundred and twenty eight catalogued items, of which twenty-one were Cezannes, twenty-two Van Goghs, forty-six Gauguins, a few Vlamincks, Derains and Frieszs and twenty-two Matisses, covering painting, drawing and sculpture.

Helping Fry organise the event, art critic Desmond MacCarthy had some inkling of the potential public explosion that was to follow and welcomed it, expecting “howls of derision,” as “the cat has been let out of the bag” and “the more it jumps the better.” Critic Frank Rutter had already used the term “Post-Impressionist” about the work of Othon Friesz in that October’s Art News and pressure from the media forced a quick decision regarding the exhibition’s name; in fact the whole show was put together in haste, with preparations lasting until four in the morning of Press day, to which MacCarthy walked as if to “the gallows.”

Matisse's portrait of his wife

Then they simply had to wait and see what the reactions would be. The first rumblings came from the show’s eminent patrons: Sir Charles Holroyd, director of the National Gallery asked that his name be removed from publicity on seeing the paintings and the Duchess of Rutland wrote to MacCarthy that she was “horrified” at being associated with the exhibition. A slightly less extreme reaction came from Charles Holmes, Slade Professor at Oxford, whose lukewarm guide went on sale at the exhibition, vaguely praising Cezanne and granting “in the arts, I am inclined to think that a stimulus of any kind is healthy.” Chasing a sensational headline, critic Robert Ross misidentified “a wide-spread plot to destroy the whole fabric of European painting,” another commented that “the exhibition is either an extremely bad joke or a swindle” and at the Slade, Professor Frederick Brown broke off his long standing friendship with Fry and students were warned to stay away for fear of contamination. The anonymous critic of the Connoisseur regretted that “men of talent…should waste their lives in spoiling good acres of canvas when they would have been better employed in stone breaking for the roads.”

But there was no going back now. Londoners were let loose with howls of derision upon works that a century later would be recognised and loved world-wide. The spectacle of art was treated much like any of the sensational shows to be visited at Olympia or Alexandra Palace as the critics recognised: “the British public will flock to the new sensation and laugh, marvel or rage…” for their amusement. Their behaviour was not unlike that of the stalls at a music hall. One critic used the analogy of dogs and music, “it makes them howl but they can’t keep away.” He had overheard the paintings described as “nightmares” and the “ceaseless hee-haw” of laughter, while the Observer described “the majority of the pictures…are not things to live with.” The Illustrated London News tried to capture the range of public responses: “some who point the finger of scorn, some who are in blank amazement or stifle the loud guffaw; some who are angry; some who sleep.”

Gauguin's controversial yellow Christ

Whilst some still persisted in seeing these new works as “post-savages…apaches of art” whose work belongs “on the pavement,” according to one letter sent into the New Age magazine, reactions did mellow after the initial weeks. By January 1911, the Daily Graphic was able to report “the general attitude was one of admiration and of regret that an exhibition which has furnished so much food for discussion must close.” V.H.Mottram attended the exhibition “as unbiased as anyone could…owing to the newspapers” and expecting to “be made to laugh,” which he did, “at the stupidity of the comments made in my presence by the other visitors.” Douglas Fox Pitt reminded readers that “all art movements have grown out of difference” and the inability to see the beauty in Cezanne indicated “a defective aesthetic sense.”

The public’s reactions had not been a surprise. Stirred by the comments and cartoons in the National Press, Londoners of all classes had gone along to the Grafton Galleries expecting to be amused and were not disappointed. With artistic tastes dictated by the Royal Academy and favouring the representational and heroic, it is not surprising that the subject matter and brush work of artists like Van Gogh and the colours of Gauguin and Cezanne were not instantly accepted. Works that appeared to be simplistic, immediate and rule-breaking threatened the powerful Edwardian hierarchy that was already crumbling and tapped into middle and upper class fears about the blurring of social boundaries. Teaching in London’s art schools had favoured the “draw for seven years – learn anatomy and chemistry and the use of the stump,” approach derided by Vanessa Bell. Once the masses had seen the Post-Impressionists, the message was spreading that an expensive education and social connections were not necessary in order to paint. What was needed instead was passion and creativity.

Van Gogh

The furore died down as quickly as it had arisen. Some new scandal came along in the papers and some other taboo of Edwardian society was being threatened. By the time Fry bravely mounted his follow up exhibition in October 1912, the participants and public had a far better idea of what to expect. Still, Londoners of all classes had not changed their views significantly. Cutting his honeymoon with Virginia short, Leonard Woolf hurried home to help as nine out of ten visitors were still roaring with laughter at the Matisses, Picassos and Cezannes. Fifty years later, Woolf particularly recalled that “every now and then some red-faced gentleman, oozing the undercut of the best beef and the most succulent of chops, carrying his top hat and grey suede gloves, would come up to my table and abuse the pictures and me with the greatest rudeness.”

Initial reactions might have been extreme but for Londoners, Fry’s exhibition was the start of an immense change. Today the influence of artists like Picasso and Gauguin, Matisse and Cezanne is impossible to underestimate: their challenge to the artistic conventions has infiltrated all aspects of design and injected colour and freedom into the stagnating Edwardian art world. Our world is one of bright colours, broached boundaries, immediacy and multi-dimensional media. Without them, the achievements of modern leaders in the field such as Richard Wright and Rachel Whiteread, Mark Leckey and Tracey Emin would not have been possible. In 1910, Virginia Woolf was right to describe the experience as provoking a change in “human character”; a century on, with the popularity and accessibility of the capital’s galleries and the incredible range of works on display, Fry’s legacy can be felt daily by Londoners in the Twenty-First Century. If only Fry were able to come and take a walk around the Royal Academy today

Saturday, 14 January 2012

Feasts from the Past

I love browsing through old menu cards; here's a few I've found recently.

A menu card for lunch at Trinity College Cambridge, 30 January 1899, which I have vicariously enjoyed despite the years that have passed since its creation. The autumn of the same year saw the arrival of many of the students who were to form the Bloomsbury group: Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Thoby Stephens and others. Judging by the image of the exploding champagne bottle at the top, it looks as if it may have been a riotous affair.

MENU

Potages

Consomme Jardiniere

Bonne Femme

Poisson

Filets de soles, sauce Tartare

Entree

Caneton aux olives

Releve

Selle de Mouton

Croquettes de pommes

Choux de mer

Roti

Faisons

Salade

Entrement

Pudding au Caramel

Becasse Ecossaise

Dessert

In April 1921, the Royal College of Art Student Common Room offered a dinner at the Boulogne Restaurant in Gerard Street, with the French theme continued with an illustration of a buxom looking jolie femme by the sea side:

MENU

Hors d'Oeuvre varies

Creme Milanaise

Filet de Hallibut Robert

Pomme nature

Quartier de mouton demi-glace

Choux fleur - Pomme au Four

Poulet au jus

Salade

Glace Melba a la Student

a dish we all like to feed upon

fromage - radis

cafe noir

On Christmas Day 1950, the Cumberland Hotel offered its young diners a special menu, where the usual traditional fare was gratuitously linked with various nursery rhyme characters, all presented in the teeth of a friendly-looking giraffe:

CHILDREN'S GALA LUNCHEON

Creme Miss Muffett

Veloute Three Blind Mice

Turkey Jack and Jill

Brussel Sprout Little Bo Peep

Potatoes Peter Pan

Pudding Tommy Tucker

Mince Pie Humpty-Dumpty

Yule Tide Log Queen of Hearts

A menu card for lunch at Trinity College Cambridge, 30 January 1899, which I have vicariously enjoyed despite the years that have passed since its creation. The autumn of the same year saw the arrival of many of the students who were to form the Bloomsbury group: Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Thoby Stephens and others. Judging by the image of the exploding champagne bottle at the top, it looks as if it may have been a riotous affair.

MENU

Potages

Consomme Jardiniere

Bonne Femme

Poisson

Filets de soles, sauce Tartare

Entree

Caneton aux olives

Releve

Selle de Mouton

Croquettes de pommes

Choux de mer

Roti

Faisons

Salade

Entrement

Pudding au Caramel

Becasse Ecossaise

Dessert

In April 1921, the Royal College of Art Student Common Room offered a dinner at the Boulogne Restaurant in Gerard Street, with the French theme continued with an illustration of a buxom looking jolie femme by the sea side:

MENU

Hors d'Oeuvre varies

Creme Milanaise

Filet de Hallibut Robert

Pomme nature

Quartier de mouton demi-glace

Choux fleur - Pomme au Four

Poulet au jus

Salade

Glace Melba a la Student

a dish we all like to feed upon

fromage - radis

cafe noir

On Christmas Day 1950, the Cumberland Hotel offered its young diners a special menu, where the usual traditional fare was gratuitously linked with various nursery rhyme characters, all presented in the teeth of a friendly-looking giraffe:

CHILDREN'S GALA LUNCHEON

Creme Miss Muffett

Veloute Three Blind Mice

Turkey Jack and Jill

Brussel Sprout Little Bo Peep

Potatoes Peter Pan

Pudding Tommy Tucker

Mince Pie Humpty-Dumpty

Yule Tide Log Queen of Hearts

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)